Howard Hughes is probably one of the more interesting characters in American history. From oil heir to aviation magnate to film producer, there was hardly an industry Hughes didn't have a hand in. Combined with several well-publicized scandals, all of this makes for a legacy that won't soon be forgotten.

The Hughes family made their fortune in 1909 when Howard Hughes Sr. invented a rotary bit for drilling oil wells. With his family's extreme wealth, young Howard Hughes Jr. did not need to pursue any career. But at an early age, he displayed an interest in engineering and had a talent for it!

He pursued this interest at the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, and at the Rice Institute of Technology, Houston. Tragically, during his studies, both of Hughes' parents died. In 1924, he left school and took control of his father's business, Hughes Tool Company, in Houston.

But running the family business did not stop Hughes from pursuing his life-long interest in aviation. In the 1930s, he began to follow his passion seriously, and in 1932 the Hughes Aircraft Company was established.

Operated as a subsidiary of Hughes Tool Company, Hughes' aircraft company quickly outgrew its original location in a rented hangar in Burbank, California.

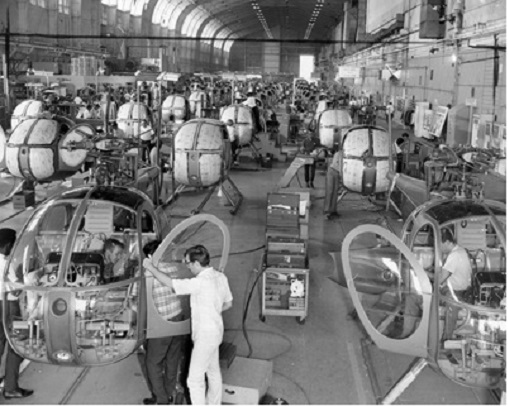

During this time, World War II was developing in Europe. As it became increasingly likely that the U.S. would become involved, the demand for aircraft manufacturing increased. To meet this increased demand, Hughes Aircraft began to research and produce D-2 medium-range bombers.

A lover of speed, Hughes designed the plane to reach a record-breaking speed of 450 miles per hour. It would also hold a crew of five and be constructed of plywood.

While he did not have a government contract for the development of these planes, Hughes was confident that the D-2 would launch the success of Hughes Aircraft. Even after the U.S. entered the war in 1941, Hughes continued research and development for the D-2. While the planes were not used in war, they would eventually be redesigned as the XF-11 and become an innovative photo-reconnaissance plane.

After the war, the company began to experience more tremendous success. It developed military electronics under its new general manager Harold C. George, a retired Air Force lieutenant general.

It became clear to company leadership that their future was in advanced military electronics, not aircraft manufacturing.

By 1950, the company was beginning to turn a large profit and had over 5,000 employees. Two years later, the Korean War caused an increase in demand for electronic weapons and interceptor systems. In three years, their employee numbers had grown to 15,000, and their net earnings jumped from $400,000 to $5.3 million.

While things were going wonderfully for Hughes professionally, personally, he was in a nose-dive. Suffering from an diagnosed mental illness, his increasingly erratic behavior caused concern amongst his investors and his two leading scientists.

Hughes' developed a complex solution to this problem; He would divest himself of controlling interest and grant profits to the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). This would turn Hughes Aircraft into a subsidiary of the foundation and funnel proceeds into medical research. A new executive team was chosen to run the company. By 1953, Hughes was no longer involved in the active management of the company.

In his final years, the billionaire became even more obsessed with privacy. He continually moved from one house to another and only allowed particular people to see him. Hughes eventually succumbed to his mental illness and died at the age of 70 in his airplane while en route from Acapulco to Houston.

One of Hughes' last requests was that he be remembered for his contributions to aviation. Looking at the strides and progress made by today's aerospace industry-many based on Hughes' work—the aerospace world is honoring that request.